El Salvador Certified Malaria-Free

The World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed the Republic of El Salvador became the first country in Central America was awarded a certification of malaria elimination.

The WHO certification announced on February 25, 2021, follows more than 50 years of commitment by the Salvadoran government to ending the disease in a country hospitable to malaria.

Certification of malaria elimination is granted by WHO when a country has proven, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the chain of indigenous transmission has been interrupted nationwide for at least the previous three consecutive years.

Except for one outbreak in 1996, El Salvador steadily reduced its malaria burden over the last three decades. Between 1990 and 2010, the number of malaria cases declined from more than 9000 to 26. The country has reported zero indigenous cases of the disease since 2017.

“For decades, El Salvador has worked hard to wipe out malaria and the human suffering that it generates,” said Dr. Carissa F. Etienne, Director of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the WHO’s regional office for the Americas, in a press statement.

“Over the years, El Salvador has dedicated both the human and financial resources needed to succeed. This certification today is a life-saving achievement for the Americas.”

El Salvador is the third country to have achieved malaria-free status in recent years in the WHO Region of the Americas, following Argentina in 2019 and Paraguay in 2018.

Seven countries in the region were certified from 1962 to 1973. Globally, a total of 38 countries and territories have reached this milestone.

El Salvador’s anti-malaria efforts began in the 1940s with mechanical control of the malaria vector – the mosquito – through the construction of the first permanent drains in swamps, followed by indoor spraying with the pesticide DDT.

In the mid-1950s, El Salvador established a National Malaria Program (CNAP) and recruited a network of community health workers to detect and treat malaria across the country. The volunteers, known as “Col Vol,” registered malaria cases and interventions. The data, entered into health information systems by vector control personnel, allowed for strategic and targeted responses across the country.

By the late 1960s, progress had slowed as mosquitoes developed resistance to DDT. An expansion in the country’s cotton industry is thought to have fueled a further rise in malaria cases.

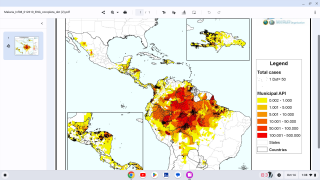

Throughout the 1970s, there was a surge of migrant laborers on cotton estates in coastal areas near mosquito breeding sites, in addition to discontinued use of DDT. El Salvador experienced a resurgence of malaria, reaching a peak of nearly 96,000 cases in 1980.

With the support of PAHO, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the US Agency for International Development (USAID), El Salvador successfully reoriented its malaria program, which led to improved targeting of resources and interventions based on the geographic distribution of cases.

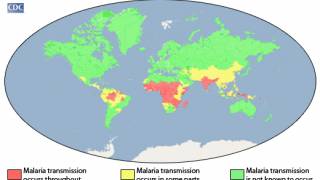

The risk for acquiring malaria differs substantially from traveler to traveler and from region to region, even within a single country.

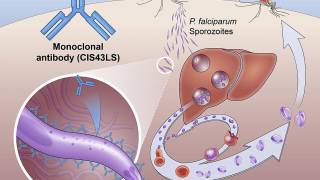

More than a dozen malaria vaccine candidates are now in clinical development, and one, GSK Biologicals’ RTS,S, has completed Phase III clinical testing.

Europe’s medicine agency approved the RTS,S vaccine in July 2015, with a recommendation that it be used in Africa for babies at risk of getting malaria.

RTS, S/AS01 is a recombinant vaccine candidate consisting of the P. falciparum circumsporozoite protein from the pre-erythrocytic stage. Mosquirix does not provide complete protection against malaria caused by P. falciparum.

Vax-Before-Travel publishes research-based malaria vaccine news.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee