Single-Dose Polio Vaccination is a Holy Grail

A new, nanoparticle vaccine which delivers multiple doses in just one injection, could make it easier to immunize children in remote regions.

Currently, for people to be protected, the inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) must be administered more than 2 times, with a 1–2 month gap.

To create a single-injection vaccine, an MIT research team encapsulated the inactivated polio vaccine in a biodegradable polymer, known as PLGA.

This polymer can be designed to degrade after a certain period of time, allowing the researchers to control when the vaccine is released.

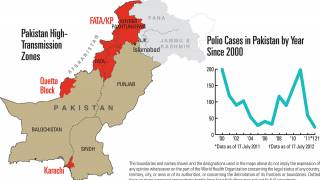

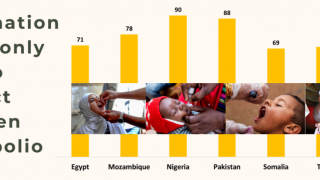

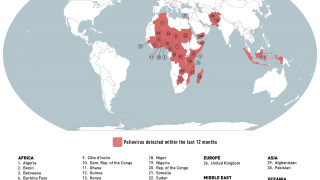

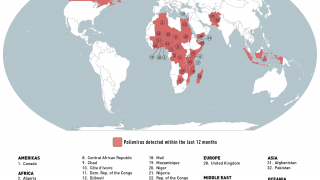

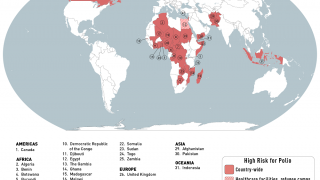

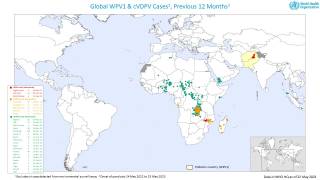

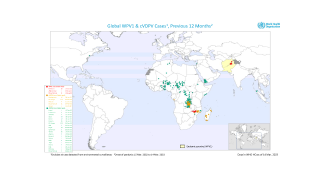

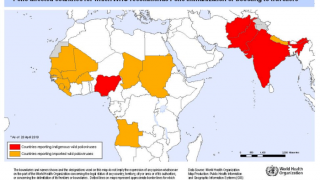

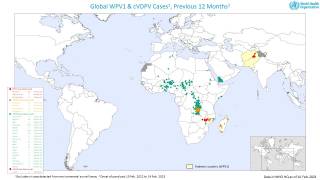

Potentially, this vaccine could target the poliovirus, which has not yet been eliminated worldwide.

“There’s always a little bit of vaccine that’s left on the surface or very close to the surface of the particle, and as soon as we put it in the body, whatever is at the surface can just diffuse away. That’s the initial burst,” these researchers said in a press release.

“Then the particles sit at the injection site and over time, as the polymer degrades, they release the vaccine in bursts at defined time points, based on the degradation rate of the polymer.”

The researchers had to overcome one major obstacle that has stymied previous efforts to use PLGA for polio vaccine delivery: The polymer breaks down into byproducts called glycolic acid and lactic acid, and these acids can harm the virus so that it no longer provokes the right kind of antibody response.

To prevent this from happening, the MIT team added positively charged polymers to their particles. These polymers act as “proton sponges,” sopping up extra protons and making the environment less acidic, allowing the virus to remain stable in the body.

To deliver more than two doses, the researchers say they could design particles that release vaccine at injection and one month later, and mix them with particles that release at injection and two months later, resulting in three overall doses, each a month apart.

The polymers that the researchers used in the vaccines are already FDA-approved for use in humans, so they hope to soon be able to test the vaccines in clinical trials.

***Find a Clinical Trial Here***

“I think the beauty of the paper is that the traditional microparticle formulation design principles for antigen stabilization are applicable to the delivery of a very complex antigen system. Single dose vaccination for developing world applications is a Holy Grail, and they are getting close,” says David Putnam, a professor of biomedical engineering and chemical and biomolecular engineering at Cornell University, who was not involved in the research.

There are no medicines to treat poliovirus. And, in about 1 percent of polio cases, the virus enters the nervous system, where it can cause paralysis.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), to eradicate polio, vaccination programs must reach children in remote areas to give them multiple vaccine injections required to build up immunity.

“Having a one-shot vaccine that can elicit full protection could be very valuable in being able to achieve eradication,” says Ana Jaklenec, a research scientist at MIT’s Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, and one of the senior authors of this paper.

The first polio vaccine, called the Salk vaccine, was developed in 1953.

The Salk vaccine consists of an inactivated version of the virus, which is usually given as a series of two to four injections, beginning at 2 months of age.

In 1961, an oral vaccine was developed, which offers some protection with only one dose, but is more effective with two to three doses.

The oral vaccine, which consists of a virus that has reduced virulence but is still viable, has been phased out in most countries because in very rare cases, it can mutate to a virulent form and cause infection.

Unfortunately, because it is easier to administer, the oral vaccine is still used in some developing countries.

For polio eradication efforts to succeed, the oral vaccine must be completely phased out, said these MIT researchers.

“The goal is to ensure that everyone globally is immunized,” Jaklenec says.

“Children in some of these hard-to-reach developing world locations tend to not get the full series of shots necessary for protection.”

The researchers are also working on applying this approach to create stable, single-injection vaccines for other viruses, such as Ebola and HIV.

The research was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee