'There Is An Ongoing Risk of International Spread of Polio’

The 23rd meeting of the World Health Organization (WHO) Emergency Committee under the International Health Regulations (IHR) regarding the spreading of poliovirus was convened on December 11, 2019, to address ongoing polio outbreaks in various countries.

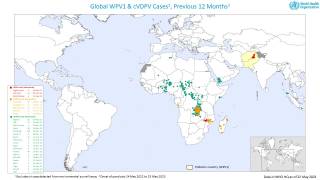

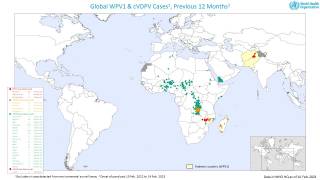

Announced in a press release on January 7, 2020, the Emergency Committee reviewed the data on wild poliovirus (WPV1) and circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses (cVDPV) from various countries, which is as follows:

Wild poliovirus

The Committee remains gravely concerned by the significant increase in WPV1 cases globally reaching 113, as of December 11, 2019, compared to 28 for the same period in 2018.

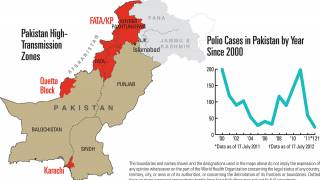

In Pakistan transmission continues to be widespread, as indicated by both AFP (acute flaccid paralysis) surveillance and environmental sampling. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province continues to be of particular concern.

The issues noted previously by the Committee, including the refusal by individuals and communities to accept vaccination, and problems with the politicization of the national polio program are still being addressed. Added pressure is now on the program due to confirmation of the detection of cVDPV2 in several Pakistan provinces.

The Committee noted that based on the sequencing of viruses, there were recent instances of international spread of viruses from Pakistan to Afghanistan and also from Afghanistan to Pakistan.

The recent increased frequency of WPV1 international spread between the two countries suggests that rising transmission in Pakistan and Afghanistan correlates with increased risk of WPV1 exportation beyond the single epidemiological block formed by the two countries.

In Afghanistan, the risk of a major upsurge of cases is growing, with other parts of the country that have been free of WPV1 for some time now, are at-risk of outbreaks. This would again increase the risk of international spread. Major efforts must be made to improve access if eradication efforts are going to progress.

The Committee noted the continued cooperation and coordination between Afghanistan and Pakistan, particularly in reaching high-risk mobile populations that frequently cross the international border and welcomed the all-age vaccination now being taken at key border points between the two countries.

In Nigeria, there has been no WPV1 detected for 3 years, and it is possible that the African Region may be certified WPV free in 2020. The certification of WPV3 eradication was also welcomed by the committee and underlines that polioviruses can be eradicated.

Vaccine derived poliovirus

The rapid emergence of multiple cVDPV2 strains in several countries is unprecedented and very concerning, and not yet fully understood.

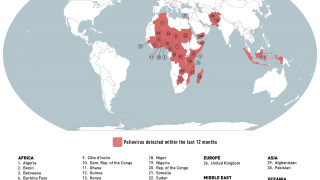

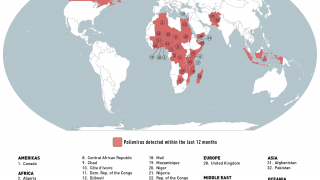

The multiple cVDPV outbreaks in 4 WHO regions (African, Eastern Mediterranean, South-east Asian and Western Pacific Regions) are very concerning, with seven new countries reporting outbreaks since the last meeting (Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Malaysia, Pakistan, Philippines, Togo, and Zambia).

Since the last meeting, cVDPV2 has spread through West Africa and the Lake Chad area, reaching Cote d’Ivoire, Togo, and Chad, and cVDPV1 has spread from the Philippines to Malaysia.

The Committee strongly supports the development and proposed Emergency Use Listing of the novel OPV2 vaccine which should become available mid-2020, and which it is hoped will result in no or very little seeding of further outbreaks.

In conclusion, the Committee unanimously agreed that the risk of international spread of poliovirus remains a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and recommended the extension of Temporary Recommendations for a further 3 months.

The committee recognizes the concerns regarding the lengthy duration of the polio PHEIC but concludes that the current situation is extraordinary, with clear ongoing risk of international spread and ongoing need for a coordinated international response.

The Committee considered the following factors in reaching this conclusion:

- The rising risk of WPV1 international spread: The progress made in recent years appears to have reversed, with the committee’s assessment that the risk of international spread is at the highest point since 2014 when the PHEIC was declared. This risk assessment is based on the following:

- the WPV1 exportation in 2019 from Pakistan to Iran and to Afghanistan, and more recently spread from Afghanistan to Pakistan;

- the ongoing rise in the number of WPV1 cases and positive environmental samples in Pakistan, and to a lesser extent Afghanistan;

- the quickly increasing cohort of unvaccinated children in Afghanistan, with the risk of a major outbreak imminent if nothing is done to access these children;

- the urgent need to overhaul the leadership and strategy of the program in Pakistan, which although already commenced, is likely taking some time to lead to more effective control of transmission and ultimately eradication;

- increasing community and individual resistance to the polio program.

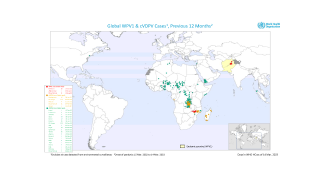

- The rising risk of cVDPV international spread: The clearly documented spread in recent months of cVDPV2 from Nigeria to Chad, Cote d’Ivoire and Togo, and between Philippines and Malaysia demonstrate the unusual nature of the current situation, as an international spread of cVDPV in the past has been very infrequent. The emergence of cVDPV2 in Zambia, which had not used mOPV2, raises further concern. The risk of new outbreaks in new countries is considered extremely high, even probable. The outbreak of cVDPV1 in Malaysia in a cross-border population shared between Malaysia, Philippines and Indonesia and which is often unreached by government immunization programs is an example of how border populations are at special risk.

- Falling PV2 immunity: Global population mucosal immunity to type 2 polioviruses (PV2) continues to fall, as the cohort of children born after OPV2 withdrawal grows, exacerbated by poor coverage with IPV particularly in some of the cVDPV infected countries.

- Multiple outbreaks: The evolving and unusual epidemiology resulting in rapid emergence and evolution of cVDPV2 strains is extraordinary and not yet fully understood and represents an additional risk that is yet to be quantified.

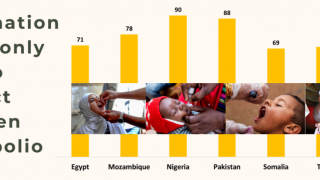

- Weak routine immunization: Many countries have weak immunization systems that can be further impacted by various humanitarian emergencies, and the number of countries in which immunization systems have been weakened or disrupted by conflict and complex emergencies poses a growing risk, leaving populations in these fragile states vulnerable to outbreaks of polio.

- Surveillance gaps: The appearance of highly diverged VDPVs in the Philippines, Somalia, and Indonesia are examples of inadequate polio surveillance, heightening concerns that transmission could be missed in various countries. Furthermore, the missed transmission in China for a year illustrates that even countries with generally good surveillance can miss VDPV transmission.

- Lack of access: Inaccessibility continues to be a major risk, particularly in several countries currently infected with WPV or cVDPV, i.e. Afghanistan, Nigeria, Niger, Somalia, Myanmar, and Indonesia, which all have sizable populations that have been unreached with polio vaccine for prolonged periods.

- Population movement: The risk is amplified by population movement, whether for family, social, economic or cultural reasons or in the context of populations displaced by insecurity and returning refugees. There is a need for international coordination to address these risks. A regional approach and strong crossborder cooperation are required to respond to these risks, as much international spread of polio occurs over land borders.

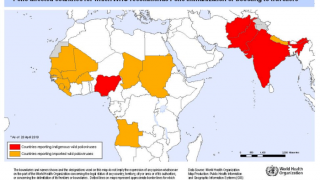

The Committee provided the Director-General with the following advice aimed at reducing the risk of international spread of WPV1 and cVDPVs, based on the risk stratification as follows:

- States infected with WPV1, cVDPV1 or cVDPV3, with a potential risk of international spread.

- States infected with cVDPV2, with the potential risk of international spread.

- States no longer infected by WPV1 or cVDPV, but which remain vulnerable to re-infection by WPV or cVDPV.

Criteria to assess States as no longer infected by WPV1 or cVDPV:

- Poliovirus Case: 12 months after the onset date of the most recent case PLUS one month to account for case detection, investigation, laboratory testing and reporting period OR when all reported AFP cases with onset within 12 months of the last case have been tested for polio and excluded for WPV1 or cVDPV, and environmental or other samples collected within 12 months of the last case have also tested negative, whichever is the longer.

- Environmental or other isolation of WPV1 or cVDPV (no poliovirus case): 12 months after the collection of the most recent positive environmental or other samples (such as from a healthy child) PLUS one month to account for the laboratory testing and reporting period.

- These criteria may be varied for the endemic countries, where more rigorous assessment is needed in reference to surveillance gaps (e.g. Borno State, Nigeria)

Once a country meets these criteria as no longer infected, the country will be considered vulnerable for a further 12 months. After this period, the country will no longer be subject to Temporary Recommendations, unless the Committee has concerns based on the final report.

TEMPORARY RECOMMENDATIONS

States infected with WPV1, cVDPV1 or cVDPV3 with the potential risk of international spread are as follows:

WPV1

- Afghanistan (most recent detection 10 November 2019)

- Pakistan (most recent detection 12 November 2019)

- Nigeria (most recent detection 27 September 2016)

cVDPV1

- Indonesia (most recent detection 13 February 2019)

- Malaysia (most recent detection 26 October 2019)

- Myanmar (most recent detection 9 August 2019)

- Philippines (most recent detection 28 October 2019)

These countries should:

- Officially declare, if not already done, at the level of head of state or government, that the interruption of poliovirus transmission is a national public health emergency and implement all required measures to support polio eradication; where such declaration has already been made, this emergency status should be maintained as long as the response is required.

- Ensure that all residents and long term visitors (i.e. > four weeks) of all ages, receive a dose of bivalent oral poliovirus vaccine (bOPV) or inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) between four weeks and 12 months prior to international travel.

- Ensure that those undertaking urgent travel (i.e. within four weeks), who have not received a dose of bOPV or IPV in the previous four weeks to 12 months, receive a dose of polio vaccine at least by the time of departure as this will still provide benefit, particularly for frequent travelers.

- Ensure that such travelers are provided with an International Certificate of Vaccination or Prophylaxis in the form specified in Annex 6 of the IHR to record their polio vaccination and serve as proof of vaccination.

- Restrict at the point of departure the international travel of any resident lacking documentation of appropriate polio vaccination. These recommendations apply to international travelers from all points of departure, irrespective of the means of conveyance (e.g. road, air, sea).

- Further intensify crossborder efforts by significantly improving coordination at the national, regional and local levels to substantially increase vaccination coverage of travelers crossing the border and of high-risk crossborder populations. Improved coordination of crossborder efforts should include closer supervision and monitoring of the quality of vaccination at border transit points, as well as tracking the proportion of travelers that are identified as unvaccinated after they have crossed the border.

- Further intensify efforts to increase routine immunization coverage, including sharing coverage data, as high routine immunization coverage is an essential element of the polio eradication strategy, particularly as the world moves closer to eradication.

- Maintain these measures until the following criteria have been met: (i) at least six months have passed without new infections and (ii) there is documentation of full application of high-quality eradication activities in all infected and high-risk areas; in the absence of such documentation these measures should be maintained until the state meets the above assessment criteria for being no longer infected.

- Provide to the Director-General a regular report on the implementation of the Temporary Recommendations on international travel.

States infected with cVDPV2s, with potential or demonstrated risk of international spread:

- Angola (most recent detection 21 October 2019)

- Benin (most recent detection 15 October 2019)

- Cameroon (most recent detection 20 April 2019)

- CAR (most recent detection 6 October 2019)

- Chad (most recent detection 9 September 2019)

- Cote d’Ivoire (most recent detection 26 September 2019)

- China (most recent detection 25 April 2019)

- DR Congo (most recent detection 26 October 2019)

- Ethiopia (most recent detection 9 September 2019)

- Ghana (most recent detection 8 November 2019)

- Mozambique (most recent detection 17 December 2018)

- Niger (most recent detection 3 April 2019)

- Nigeria (most recent detection 9 October 2019)

- Philippines (most recent detection 25 October 2019)

- Somalia (most recent detection 10 November 2019)

- Togo (most recent detection 16 October 2019)

- Zambia (most recent detection 25 September 2019)

These countries should:

- Officially declare, if not already done, at the level of head of state or government, that the interruption of poliovirus transmission is a national public health emergency and implement all required measures to support polio eradication; where such declaration has already been made, this emergency status should be maintained.

- Noting the existence of a separate mechanism for responding to type 2 poliovirus infections, consider requesting vaccines from the global mOPV2 stockpile based on the recommendations of the Advisory Group on mOPV2.

- Encourage residents and longterm visitors to receive a dose of IPV four weeks to 12 months prior to international travel; those undertaking urgent travel (i.e. within four weeks) should be encouraged to receive a dose at least by the time of departure.

- Ensure that travelers who receive such vaccination have access to an appropriate document to record their polio vaccination status.

- Intensify regional cooperation and crossborder coordination to enhance surveillance for prompt detection of poliovirus, and vaccinate refugees, travelers, and crossborder populations, according to the advice of the Advisory Group.

- Further intensify efforts to increase routine immunization coverage, including sharing coverage data, as high routine immunization coverage is an essential element of the polio eradication strategy, particularly as the world moves closer to eradication.

- Maintain these measures until the following criteria have been met: (i) at least six months have passed without the detection of circulation of VDPV2 in the country from any source, and (ii) there is documentation of full application of high-quality eradication activities in all infected and high-risk areas; in the absence of such documentation these measures should be maintained until the state meets the criteria of a ‘state no longer infected’.

- At the end of 12 months without evidence of transmission, provide a report to the Director-General on measures taken to implement the Temporary Recommendations.

States no longer infected by WPV1 or cVDPV, but which remain vulnerable to re-infection by WPV or cVDPV:

WPV1

- none

cVDPV

- Kenya cVDPV2 (last environmental positive specimen 21 March 2018)

- PNG cVDPV1 (last environmental positive specimen 6 November 2018)

Additional considerations

- Preparedness - The committee urged all countries, particularly those in Africa, to be on high alert for the possibility of cVDPV2 importation and respond to such importations as a national public health emergency. This means countries should ensure polio surveillance can rapidly detect cVDPV2, and plans are in place to respond rapidly with well planned and executed mOPV2 campaigns, and with strict procedures to ensure unused vials are returned and managed so that inappropriate or accidental use is avoided.

- International Coordination - Unprecedented levels of international spread of cVDPV require urgent coordinated control measures at regional and sub-regional levels. The committee strongly encourages countries to do more in support of cross border actions, such as sharing of surveillance and other data, synchronizing campaigns and where possible ensure vaccination of international travelers.

- Emergency Response – The committee noted the endorsement of SAGE for the accelerated clinical development of novel OPV2 and its assessment under the WHO Emergency Use and Listing (EUL) procedure, which can be used in a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC), and added its support to ensure the supply of monovalent OPV2.

- Financing - The number of outbreaks is proving to be costly to manage, and the committee urged affected countries to prioritize polio control as a public health emergency and ensure adequate domestic funding is available for an effective response. The committee urged affected countries to mobilize domestic funding to complement the GPEI resources which are being stretched by the large number of outbreaks being fought globally.

- Communication - Vaccine hesitancy is a significant factor in the spread of these outbreaks particularly certain countries including Pakistan and Angola. The committee urged countries to invest time and resources into pro-actively circumventing and countering myths and misinformation regarding vaccination is general, and rumors that arise during the course of campaigns in particular. Campaign communications need to address issues around avoiding spreading excreted Sabin-like viruses through good hygiene.

Based on the current situation regarding WPV1 and cVDPV, and the reports provided by affected countries, the Director-General accepted the Committee’s assessment and on December 19, 2019, determined that the situation relating to poliovirus continues to constitute a PHEIC, with respect to WPV1 and cVDPV.

The Director-General endorsed the Committee’s recommendations for countries meeting the definition for ‘States infected with WPV1, cVDPV1 or cVDPV3 with potential risk for international spread’, ‘States infected with cVDPV2 with potential risk for international spread’ and for ‘States no longer infected by WPV1 or cVDPV, but which remain vulnerable to re-infection by WPV or cVDPV’ and extended the Temporary Recommendations under the IHR to reduce the risk of the international spread of poliovirus, effective December 19, 2019.

Polio, or poliomyelitis, is a disabling and life-threatening disease caused by the poliovirus. The virus spreads from person to person and can infect a person’s spinal cord, causing paralysis, says the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as of October 24, 2019.

The CDC says ‘the USA has been polio-free since 1979.’

For best protection, children should get 4 doses of the Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV). This vaccine is given as a shot in the arm or leg and is very safe.

Even if you were previously vaccinated, you may need a 1-time booster shot before you travel anywhere that could put you at risk for getting polio. A booster is an additional dose of vaccine to ensure the original vaccine series remains effective.

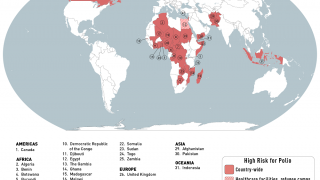

The CDC previously issued polio-related travel alerts during 2019 for various countries in Africa, Asia, and Oceania.

For additional travel vaccine information, visit CDC’s Travelers’ Health website for timely travel health information. Also find information about symptoms, vaccination, complications, and transmission of polio in this fact sheet for parents.

The CDC says ‘to see your healthcare provider for more polio vaccination information.’

International vaccine news is published by Vax-Before-Travel.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee

- WHO: Statement of the Twenty-Third IHR Emergency Committee Regarding the International Spread of Poliovirus

- CDC: Global Health- Polio

- Strategy for Control of cVDPV2, 2020 – 2021

- The safety and immunogenicity of two novel live attenuated monovalent (serotype 2) oral poliovirus vaccines in healthy adults: a

- Novel Oral Type-2 Poliovirus Vaccines Reported Safe