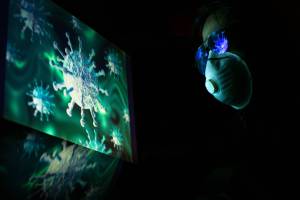

SARS-1 Coronavirus

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-1)

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus-1 (SARS-CoV-1) is a viral respiratory illness caused by a beta coronavirus (CoV). SARS-1 is a different coronavirus than the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, which was identified in late 2019. The new SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus and variants are more infectious but less fatal than its forerunner, SARS-CoV-1.

SARS-1 originated in Guangdong Province, located in southern China, in November 2002 and was found in Hong Kong in February 2003, and primarily spread to Asian countries. A report issued by Sen. Marco Rubio and staff in 2023 highlighted a study with avian influenza conducted by the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Tokyo in 2012 as an essential case study of how passaging a virus through ferrets could confer the properties needed for highly efficient transmission in humans via respiratory droplets. At the end of the SARS-1 epidemic in 2004, the cumulative total was 8,422 cases with 916 related fatalities (case fatality rate of 11%).

SARS-1 Outbreak Timeline

2003 - As of July 2003, the WHO reported 325 SARS-1 cases, and the illness spread to about 24 countries in North America, South America, Europe, and Asia in 2003.

2003 - There have been six escapes from virology labs: 1 event each in Singapore and Taiwan and four separate escapes of the coronavirus at the same laboratory in Beijing, China.

June 3, 2004 - Public Health Measures to Control the Spread of the SARS during the Outbreak in Toronto," New England Journal of Medicine.

2004 - The WHO published the 'SARS Risk Assessment and Preparedness Framework in October.' And the CDC issues a "Notice of Embargo of Civets." A SARS-like virus had been isolated from civets (captured in China's areas where the SARS outbreak originated). As a result, CDC banned the importation of civets, which remains in effect.

2005 - A pre-clinical study found chloroquine effectively inhibits SARS-CoV infection and spreads in cell culture. Similar studies describe these proteins' roles in SARS-CoV replication and potential therapeutic strategies to prevent SARS-CoV entry into target cells.

2005 - Microbiologist Kwok-yung Yuen of the University of Hong Kong and colleagues sampled monkeys, rodents, and bat species in Hong Kong's hinterlands. The SARS-like virus was found in 39% of the anal swabs collected from Chinese horseshoe bats, both eaten and used in traditional Chinese medicine. Also, around 80% of bat serum samples showed antibodies to the virus.

June 7, 20221 - Super-spreaders in infectious diseases.

SARS-CoV Research

In November 2015, the journal Nature Medicine published a study: 'A SARS-like cluster of circulating bat coronaviruses shows potential for human emergence. Furthermore, the study abstract stated, 'Our work suggests a potential risk of SARS-CoV re-emergence from viruses currently circulating in bat populations.'. This study used metagenomics data to identify a potential threat posed by the circulating bat SARS-like CoV SHC014. Because of the ability of chimeric SHC014 viruses to replicate in human airway cultures, cause pathogenesis in vivo and escape current therapeutics, there is a need for both surveillance and improved therapeutics against circulating SARS-like viruses.

On March 14, 2016, the journal PNAS published a study - SARS-like WIV1-CoV poised for human emergence - that indicates an ongoing threat posed by WIV1-related viruses and the need for continued research and surveillance.

SARS-CoV Overview

A recent study reports that human coronavirus was cultured in the 1960s from people with common cold nasal cavities. They are the 2nd leading cause of the common cold after rhinoviruseAccording to the CDC, people worldwide commonly get infected with human coronaviruses 229E, NL63, OC43, and HCDC. The discovery of bat SARS-like coronaviruses and the great genetic diversity of coronaviruses in bats have shed new light on SARS coronaviruses' origin and transmission.

Coronaviruses have four main sub-groupings: alpha, beta, gamma, and delta. SARS-CoV is a betacoronavirus, like MERS.

The U.S. CDC published a report in December 2006, concluding, 'Bats have been identified as a natural reservoir for an increasing number of emerging zoonotic viruses, including henipaviruses and variants of rabies viruses. Recently, another group independently identified several horseshoe bat species as the reservoir host for many viruses with a close genetic relationship with the coronavirus associated with severe SARS. In addition to SARS-like coronaviruses, many other novel bat coronaviruses, which belong to groups 1 and 2 of the three existing coronavirus groups, have been detected by PCR.

SARS-CoV Sources

A 2015 study suggests a potential risk of SARS-CoV re-emergence from viruses currently circulating in bat populations. The results indicate that group 2b viruses encoding the SHC014 spike in a wild-type backbone can efficiently use multiple orthologs of the SARS receptor human angiotensin-converting enzyme II (ACE2), replicate efficiently in primary human airway cells and achieve in vitro titers equivalent to epidemic strains of SARIn addition, a-CoV. In addition, a study published in 2007 found horseshoe bats are a natural reservoir for the SARS-CoV-like virus.

On January 7, 2004, Philip P. Pan with the Wall Street Journal reported authorities in southern China began culling thousands of civet cats based on an unpublished study suggesting the weasel-like animal may be the source of the SARS virus.

NOTE: This page's content is sourced from the CDC, WHO, and the Precision Vax news network. Healthcare providers last fact-checked this information.