Neonatal Herpes Acquired From Mom Can Be Fatal

When most people hear the term herpes, they first think of cold sores or perhaps genital infections.

Both are associated with the herpes simplex virus (HSV), which is not curable, but can be helped with antiviral drugs, such as Acyclovir.

There is a less recognized form of herpes called neonatal herpes virus (nHSV), which can infect newborns often leading to brain damage and death.

There are three forms of nHSV infection: disease localized to the skin, eye, and mouth; encephalitis; and disseminated disease.

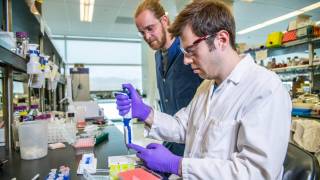

A new study published on April 10, 2019, by a team of researchers from Dartmouth's Geisel School of Medicine, is offering new insights into neonatal herpes, its impact on developing nervous systems, and how newborns can be protected from the disease.

This study found that maternal immunization with an HSV-2 replication-defective vaccine candidate, dl5-29, led to the transfer of HSV-specific antibodies into neonatal circulation that protected mice against nHSV.

"One problem in infants (with neonatal herpes) is that it's very difficult to diagnose, often they're given antibiotics to treat what is thought to be a bacterial infection," explains David Leib, Ph.D., professor and chair of microbiology and immunology at Dartmouth, in a press release.

"By the time the (diagnosis) mistake is realized, and they're given antivirals, it's too late to save their lives or to save their brains from long-term neurological damage.”

"This (damage) can manifest as speech and learning problems, anxiety, motor issues, and problems with their hearing and vision."

These Dartmouth researchers were able to test the efficacy of a live attenuated dl5-29 HSV vaccine candidate from the Knipe Lab in a neonatal mouse model, by administering the vaccine to female mice, then mating those females to generate offspring.

"What we discovered was that when we challenged the newborn mice with the virus, they were protected due to the mothers having been vaccinated," says Dr. Leib.

"Similarly, a different set of newborn mice were protected after we gave their moms a shot of HSV-specific antibodies."

"So, we were able to show that with both active and passive immunity administered to the mothers, we could protect the offspring from this neurological disorder," says Dr. Leib.

The Dartmouth researchers were also able to obtain human longitudinal serum samples from mothers, newborns, and young children to test for HSV antibodies and confirm the validity of their mouse model.

The work builds on findings from a study published in 2017 in the journal mBio by Dr. Leib and his research team that found that antibodies produced by adult women or female mice were able to migrate easily to the nervous systems of their unborn babies--giving them immunity from the virus.

However, there are two scenarios that are particularly dangerous for newborns, says Dr. Leib.

"One is when a mother acquires genital herpes late in pregnancy, but does not yet have a mature immune response she can pass to the baby," he says.

"The other, which is still not well-known, is when a mother who is completely herpes-free delivers a baby, who is then exposed to the virus in their community, usually through a kiss by a well-meaning family member."

In a unique aspect of this study, investigators were able to measure not only mortality but also neurological consequences of infection in mice who acquired the virus.

Dr. Leib's lab members Chaya Patel, a graduate student and first author on the paper, and Sean Taylor, a research assistant, in consultation with Dartmouth's Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, developed a behavioral test for infection-induced, anxiety-like behavior.

"They set up what's called an open field test, by constructing an open chamber with a GoPro camera mounted on the top, so they could record the movements and behavior of the mice," explains Dr. Leib.

"What we found was that mice who were infected and not protected by their mothers had significantly higher levels of anxiety-like behavior, consistent with the idea that they had brain damage."

This research is important since a recent analysis of large-population databases provide insight into the incidence of nHSV disease in the USA.

Whereas the incidence is low, namely 5.24 cases per 10,000 live-births, the potential morbidity and mortality from this infection remain high; adjusted mortality is about 4 percent in spite of antiviral therapy.

A February 8, 2019, NIH announcement said ‘newborn infants up to 3 months of age, who are infected with nHSV, can now be treated with Acyclovir.’

Next, Dr. Leib and his colleagues are focusing on improving the effectiveness of both the vaccine and antibodies in neutralizing the herpes virus in neonates.

The work was supported, in part, by a National Institutes of Health-funded program project (grant number P01 AI098681) between Harvard and Dartmouth, with Harvard Medical School investigators Don Coen, Ph.D., and David Knipe, Ph.D. Leib also worked with Margie Ackerman, Ph.D., associate professor at Dartmouth’s Thayer School of Engineering, on the study. No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Founded in 1797, the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth strives to improve the lives of the communities it serves through excellence in learning, discovery, and healing.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee

- Maternal immunization confers protection against neonatal herpes simplex mortality and behavioral morbidity

- Dartmouth researchers offer new insights into how maternal immunity impacts neonatal HSV

- Genital Herpes

- Neonatal Herpes Simplex Virus Infection Can Be Treated With Acyclovir

- Genital Herpes Vaccine Seeks Strategic-Options