H3N2 Mutation in Flu Vaccine Responsible for Reduced Efficacy

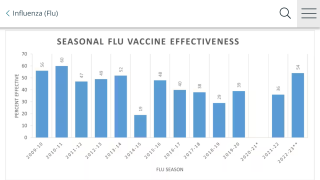

The low efficacy of last year’s influenza vaccine can be attributed to a mutation in the H3N2 strain of the virus, a new study reports.

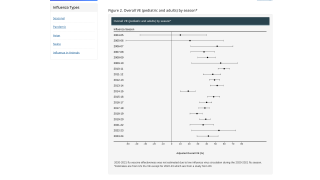

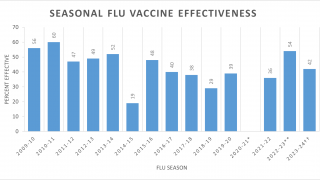

Due to the mutation, most people receiving the egg-grown vaccine did not have immunity against H3N2 viruses that circulated last year, leaving the vaccine with only about 30 percent effectiveness.

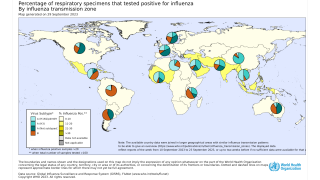

This study’s findings are similar to the Australian flu vaccines for 2017, which were reported to be only 33 percent effective against H3N2 viruses.

A major cause for this lack in effectiveness has been attributed to the egg-based vaccine production process.

Scott Hensley, PhD, an associate professor of Microbiology, in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, describes his team’s findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week.

“Our experiments suggest that influenza virus antigens grown in systems other than eggs are more likely to elicit protective antibody responses against H3N2 viruses that are currently circulating,” Dr. Hensley said.

“The 2017 vaccine that people are getting now has the same H3N2 strain as the 2016 vaccine, so this could be another difficult year if this season is dominated by H3N2 viruses again.”

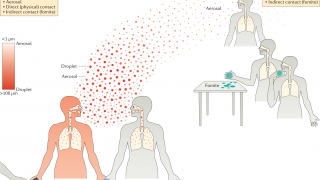

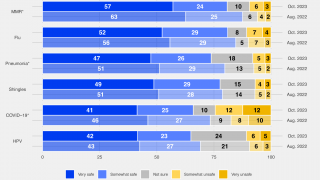

Most flu vaccine proteins are purified from a virus grown in chicken eggs, although a small fraction of flu vaccine proteins are produced in systems that do not involve eggs.

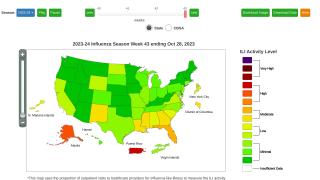

During the 2014-2015 flu season, a strain of the H3N2 virus with a different outer layer protein emerged and this version of H3N2 remains prevalent today. The 2016-2017 seasonal flu vaccine was updated to include the new version of this protein; however, Hensley’s lab found that the egg-grown version of this protein acquired a new mutation.

“Current H3N2 viruses do not grow well in chicken eggs, and it is impossible to grow these viruses in eggs without adaptive mutations,” Dr. Hensley said.

The team showed that antibodies elicited in ferrets and humans exposed to the egg-produced 2016-2017 strain did a poor job of neutralizing H3N2 viruses that circulated last year.

However, antibodies elicited in ferrets infected with the current circulating H3N2 viral strain (that contains the new protein) and humans vaccinated with a H3N2 vaccine produced in a non-egg system were able to effectively recognize and neutralize the new H3N2 virus.

“Our data suggest that we should invest in new technologies that allow us to ramp up production of influenza vaccines that are not reliant on eggs,” Dr. Hensley said.

“In the meantime, everyone should continue to get their annual flu vaccine.”

“Some protection against H3N2 viruses is better than nothing and other components of the vaccine, like H1N1 and influenza B, will likely provide excellent protection this year,” said Dr. Hensley.

Study coauthors are Seth J. Zost, Kaela Parkhouse, Megan E. Gumina, Kangchon Kim, Sebastian Diaz Perez, Patrick C. Wilson, John J. Treanor, Andrea J. Sant, and Sarah Cobey.

This work was funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01AI113047, R01AI108686, DP2AI117921, CEIRS HHSN272201400005C) and an Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the Raymond and Ruth Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee