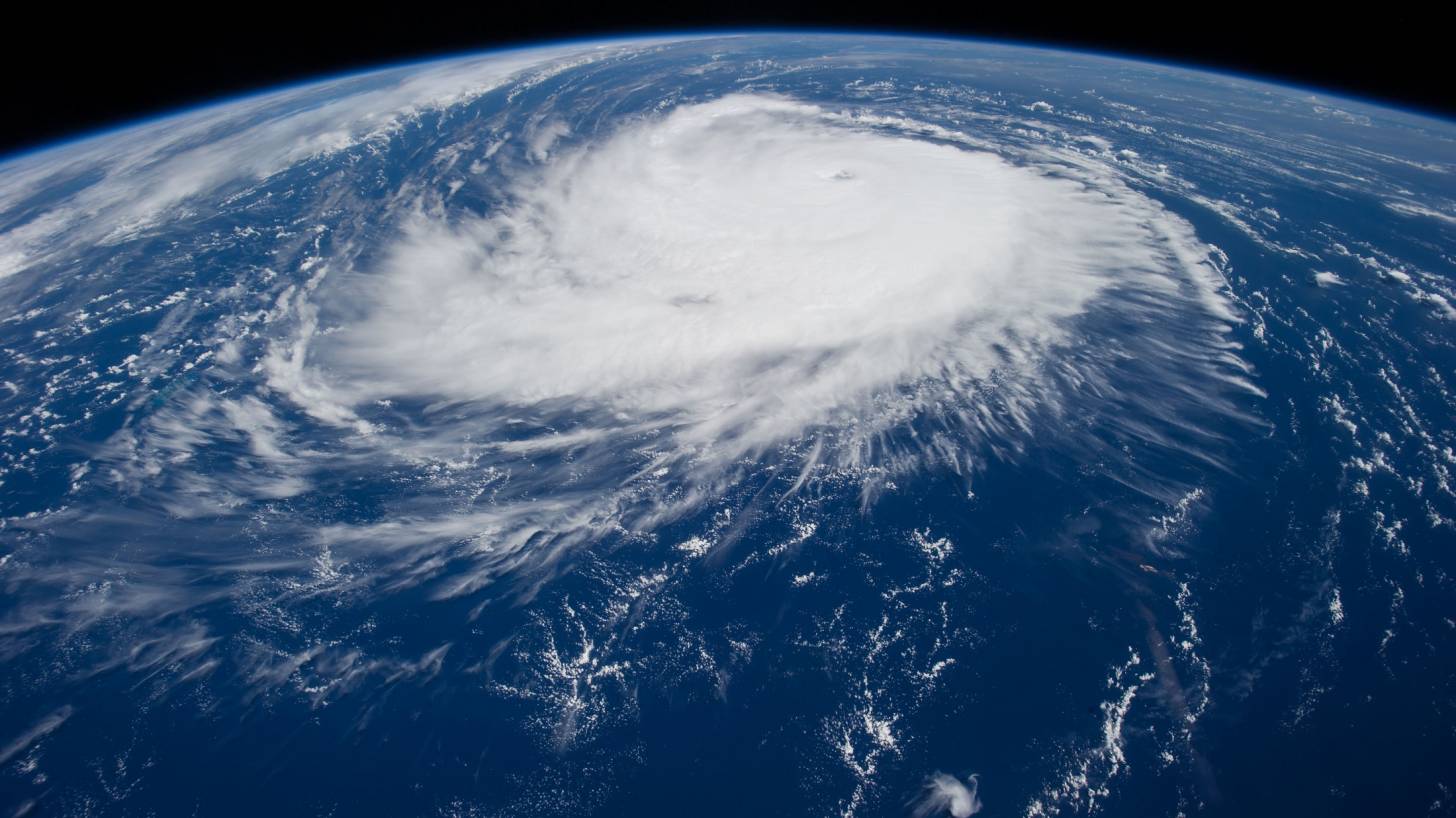

Similar to Katrina, Harvey Could Breed Zika and West Nile Viruses

On August 25, 2017, Hurricane Harvey came ashore near Corpus Christi, Texas, bringing heavy rains, winds, and surging coastal waters, creating indiscriminate devastation.

As the floodwaters recede and form pools of stagnant water, they could become breeding areas for the Aedes vexans and Aedes aegypti mosquitoes.

These mosquitoes are well known vectors for both West Nile and Zika viruses.

Many health officials are asking, “Will Harvey’s impact return viruses to the Third-coast, similar to Hurricane Katrina?’

The relationship between natural disasters and communicable diseases is often misconstrued. Previous research found that deaths from communicable diseases after natural disasters are not common.

The risk of infectious-disease outbreaks shortly after natural disasters is not as high as one might think, according to an overview published by researchers from the World Health Organization (WHO) in Emerging Infectious Diseases.

“Deaths associated with natural disasters, particularly rapid-onset disasters, are overwhelmingly due to blunt trauma, crush-related injuries, or drowning,” the WHO article stated.

The greatest disease risk, according to these WHO authors, “comes from population displacement. If people are crowded in shelters with insufficient sanitation, that could create the conditions for disease to spread.”

A 2007 study in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) journal Emerging Infectious Diseases reported that Louisiana and Mississippi did not experience an increased number of West Nile virus (WNV) cases immediately following Hurricane Katrina.

Katrina’s hurricane-force winds may have actually decreased the risk of WNV by killing birds and mosquitoes, and destroying their habitat.

However, another study published by the Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in 2008 also examined West Nile virus in the areas affected by Katrina. This study found that there were no WNV cases in Louisiana in the 3 weeks before Katrina.

But, 11 WNV cases were reported 3 weeks later.

The study authors noted a correlation with the 3 to 14 day incubation period for West Nile virus, and that the increase in the number of cases occurred despite the population loss from the extensive migration of local residents relocating away from flooded and damaged areas.

While officials don’t yet know how Harvey will impact the spread of West Nile or Zika viruses, for now, the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) is dealing with the various public health effects of the storm.

Texas has issued precautions for the public to avoid contact with floodwater, which can contain bacteria, hazardous chemicals, and dangerous debris.

The timing of Harvey is also a consideration. Texas still has many more weeks of mosquito season and they could certainly reappear before the fall weather arrives.

If populations do increase, “mostly those will be nuisance mosquitoes,” says Chris Van Deusen, a spokesman for the Texas DSHS, “However there is certainly a potential that we could see disease vectors in increasing numbers.”

Van Deusen notes that Harris County has a “very robust” mosquito-control program, and hopefully any disease carriers would be picked up in the course of normal mosquito surveillance.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee

- Will Flooding in Texas Lead to More Mosquito-Borne Illness?

- Epidemics after Natural Disasters

- Effect of Hurricane Katrina on Arboviral Disease Transmission

- Increase in West Nile Neuroinvasive Disease after Hurricane Katrina

- Floodwater Mosquitoes vs. House Mosquitoes

- DSHS Provides Flood Precautions as Hurricane Harvey Affects Texas News Release

- Epidemiology and Transmission Dynamics of West Nile Virus Disease

- Effect of Hurricane Katrina on Arboviral Disease Transmission