Hepatitis B & D: Partners in Liver Damage

A new study published by a team of Canadian researchers adds insights into how 2 types of hepatitis work together to negatively impact a human’s liver.

Located in Montreal, Canada, at the Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique (INRS), Professor Patrick Labonté and the team say they ‘have identified the role of a key process in the replication cycle of the hepatitis D virus.’

This is important news since the hepatitis D virus (HDV), also known as delta hepatitis, affects 15 to 20 million people worldwide.

To cause liver damage, HDV has a specific target. it infects only people carrying the hepatitis B virus (HBV).

As with other co-infections, the combination of hepatitis B and D causes more liver damage than hepatitis B alone.

"HDV needs HBV to survive, it's like a parasite," says researcher Patrick Labonté, in a related press release published on December 19, 2019.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), at least 5 percent of people with chronic HBV infection are also infected with HDV. And, HBV-HDV co-infection is the most severe form of chronic viral hepatitis because it progresses very quickly and can even be fatal.

“However, cure rates are low because treatments for hepatitis B are ineffective against HDV. It may seem contradictory since the virus cannot survive on its own.”

"In fact, drugs target a specific enzyme to control hepatitis B, but treatment does not completely eliminate the virus. The VHD survives normally and can continue its damage,” said Professor Labonte.

The challenge for Professor Labonté and his research team is thus to find a treatment that will fight both viruses and it seems they are on the right track.

In a study published in the Journal of Virology on November 20, 2019, the research team showed that VHD was exploiting the same cellular protein as HBV, called ATG5, to promote its development, particularly its replication in the nucleus of the host cell.

This protein is essential for what is called autophagy; a process that is used for cleaning cellular waste. In theory, autophagy should be able to destroy invaders, but most viruses, such as hepatitis C or influenza, have evolved to avoid this degradation and even use autophagy to their advantage.

"Several studies have looked at the role of autophagy in viruses, but it varies from one virus to another depending on its replication process. We are the first to determine the effect of the process on the hepatitis D virus," says Professor Labonté.

He was not surprised that ATG5 protein benefits these two hepatitis viruses since they are closely linked.

With this common protein, the autophagic process could be a solution since it is essential to the life cycle of these viruses.

However, the situation is not that simple.

"If we block autophagy, then we are blocking an important function for all cells in the body. We do not know what the long-term effects might be. Autophagy should be inhibited in a targeted and temporary manner," warns Professor Labonte.”

"Hepatitis B virus alone can cause cirrhosis or liver cancer. When combined with the hepatitis D virus, the development of these diseases happens more frequently and more rapidly," he says.

In the course of this research, Professor Labonté;'s team made an interesting discovery: some autophagy proteins travel outside their usual area.

"Autophagy usually occurs in the cell's cytoplasm, but the process contributes to the replication of the HDV genome which takes place in the nucleus. Are there any autophagic proteins present in the nucleus in the case of an infection,” wondered the researcher.

This is an area that the team is currently studying and will hopefully provide a more in-depth understanding of the role of autophagy in HDV.

Hepatitis D is transmitted to humans through percutaneous or mucosal contact with infectious blood and can be acquired either as a coinfection with HBV or as a superinfection in people with HBV infection, says the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

There is not a CDC approved a vaccine for hepatitis D, but it can be prevented in people who are not already HBV-infected, by hepatitis B vaccination.

Recent hepatitis vaccine news

- Hepatitis B Vaccine Candidate Doses 1st Patient

- Hepatitis B Immunity Among Women of Childbearing Age Decreased in 3 States

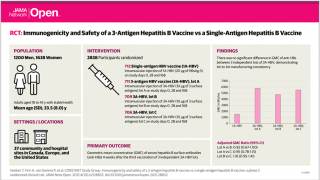

In the USA, there are 3 single-antigen vaccines and 2 combination HBV vaccines available:

Single-antigen hepatitis B vaccines: ENGERIX-B, RECOMBIVAX HB, and HEPLISAV-B

HBV combination vaccines include PEDIARIX and TWINRIX.

This research was supported by funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

The Institut national de la recherche Scientifique is the only institution in Québec dedicated exclusively to graduate-level university research and training.

Hepatitis vaccine news published by Precision Vaccinations

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee